Know about The Father of Genetics - Gregor Mendel,founder of scientific genetics

Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian monk and part-time school teacher, undertook a series of brilliant hybridisation experiments with garden peas between 1857 and 1864 in the monastery gardens and, using statistical methods for the first time in biology, established the laws of heredity, thereby establishing the discipline of genetics.

Mendel, baptised Johannes, was born on 22 July 1822 at Heinzendorf in Moravia, then part of Austria, now in the Czech Republic. He was the only son of struggling peasant farmers who also had two daughters. Initially Mendel attended the village school in Heinzendorf. There, the parish priest, Johann Schreiber, also an expert in fruit growing, recognised his talents and persuaded his parents to continue his education in spite of their limited resources. At the age of 12 he was sent to the gymnasium in Troppau where he studied for the next six years.

Mendel was assigned first to pastoral duties, and then, finding himself unsuited to this because of his shyness, to teaching in a secondary school in Znaim. However, on failing to obtain his teacher’s certificate, he was sent to the University of Vienna (1851–1853) to study natural sciences and mathematics.

It was at this time that he acquired the scientific research skills that he was later to put to such good use. In 1854, Mendel returned to teaching in Brünn but two years later again failed to obtain a teaching certificate. It is said that he withdrew from the exam because of nervous exhaustion; another account suggests that it was because of a disagreement with the examiners in botany, a disagreement that then prompted him later to undertake his famous plant breeding experiments.

Whatever the truth, this exam failure led to Mendel becoming a part-time assistant teacher, a post that provided him with plenty of time to undertake his scientific research.

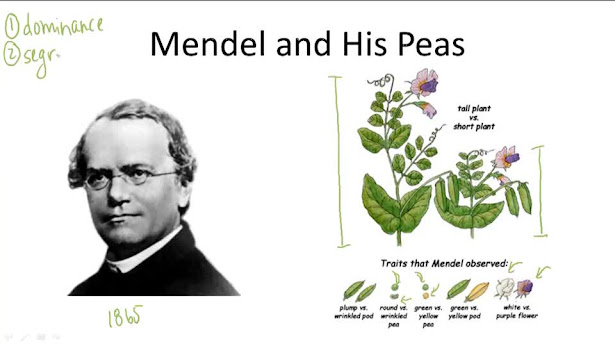

Between 1857 and 1864 Mendel undertook a series of hybridisation experiments in the Monastery’s garden, which were breathtaking for their brilliance in planning, observation, and analysis, and in interpretation of results. He was fortunate to choose the garden pea, Pisum, for his studies because it exists in separate pure lines.

Within each line, each plant is identical, although each may vary in characters such as colour or shape. In addition, peas are hermaphrodite, bearing both male and female sex cells on the same individual and able to self fertilise. Furthermore, the flowers are naturally self fertilised before the bud opens and thus before insects can intervene in the process.

In addition, the pea is an annual and great numbers can be grown in a small space. Mendel described his project in the following way in the introduction to his paper on Experiments in plant hybridization, which was presented to the Society for the Study of the Natural Sciences in Brünn in 1865.

Before Mendel, heredity had been regarded as a blending process and the offspring a dilution of the various parental characteristics. Mendel showed that the different characters in heredity followed specific laws, which could be determined by counting the diverse kinds of offspring produced from particular sets of crosses.

He established two principles of heredity now known as the law of segregation and the law of independent assortment, thereby proving the existence of paired elementary units of heredity (genes) and establishing the statistical laws governing them.

In summary, Mendel showed that inheritance depended on the combination of two unequally expressed genes which combined in an individual but never blended. In doing so, he was the first to apply a knowledge of mathematics and statistics to a biological problem.

Although copies of the Proceedings containing Mendel’s publication were sent to 133 associations of natural scientists and libraries in a number of countries, and he himself sent reprints to scholars and friends around Europe, there were only three citations of his work in the scientific literature during the next 35 years. Mendel in fact paid the price for being too far in advance of his time.

In 1868, the Abbot of St Thomas’ died and Mendel at the age of 46 was elected to succeed him as spiritual director of the monastic community. He was clearly well liked and respected by his fellow monks for his honesty, loyalty, and modesty. However, from that time on he was overwhelmed by administrative and public service duties.

In particular, he became very involved in fighting, unsuccessfully, the government on a new law to tax the monastery. In addition, he became a member of the Moravian legislature and was greatly in demand in numerous fields, religious, literary, agricultural, horticultural, humanitarian, and educational. Among the 34 societies of which he was an active member were the Austrian Zoological-Botanical Society, the Austrian Meteorological Society, the Moravian Apiary Society, and the Imperial-Royal Moravian-Silesian Agricultural Society.

At about this time he also developed backache, his eyesight began to fail, and he became overweight. He published only one further scientific paper, on hawkweed in 1869. It was of little significance. In his own words he had to “neglect completely his experimental work with plants”. He became a rather solitary figure. Towards the end of his career he wrote: “I have experienced many a bitter hour in my life. Nevertheless, I admit gratefully that the beautiful, good hours far outnumbered the others. My scientific work brought me such satisfaction, and I am convinced the entire world will recognise the results of these studies”.

The world might, but first there were to be those 35 years of neglect. Only in 1900 did three botanists, Hugo de Vries (Holland), Karl Correns (Germany), and von Tschermac (Austria), independently confirm his work. Meanwhile Francis Galton had in 1897 arrived at a statistical “law of heredity” based on observations on the pedigrees of Basset hounds. Even at the turn of the century, the recognition of Mendel’s work aroused a storm of controversy, which lasted a further 35 years.

Mendel’s use of statistics in biology was original and aroused feelings of intense hostility in certain quarters. There were even accusations that he had been guilty of falsifying his data. By the 1930s, however, the brilliance and correctness of his observations and conclusions on hereditary transmission were universally accepted.

Mendel passed away after a long and painful illness on 6 January 1884. He was 62. Postmortem examination confirmed Bright’s disease with secondary hypertrophy of the heart. So died the Right Reverend Abbot Gregor Johann Mendel, mitred prelate and companion of the Royal and Imperial Order of Francis Joseph. He was laid to rest in the Brünn central cemetery. The world has indeed come to recognise him as one of the greatest scientific biologists of all time and the father of genetics.

Post a Comment

Please do not enter any SPAM link in comment box.